Urban design is the process of shaping the physical features and functions of cities, such as buildings, streets, parks, and transportation systems. Urban design can have a significant impact on the health and well-being of urban residents, as it can influence their behavior, choices, and opportunities. In this essay, I will argue that urban design can promote physical activity and reduce the risk of chronic diseases by creating environments that encourage walking, cycling, and other forms of active transportation, and by providing access to urban green spaces, such as parks and gardens.

Physical activity and chronic diseases

Physical activity can have multiple benefits for health, such as improving cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, bone density, and mental health. Physical activity can also prevent or delay the onset of chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and some cancers. Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability worldwide, accounting for 71% of all deaths in 2016.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), insufficient physical activity is one of the main risk factors for chronic diseases. Insufficient physical activity is defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week. The WHO estimates that insufficient physical activity is responsible for 9% of premature mortality globally, and that increasing physical activity levels could prevent 1.6 million deaths per year.

However, physical activity levels are declining worldwide, especially in urban areas. The WHO reports that 23% of adults and 81% of adolescents do not meet the recommended levels of physical activity. One of the reasons for this decline is the rapid urbanization that has occurred in the past decades, which has changed the way people live, work, and move in cities.

Urban design and physical activity

Urban design can influence physical activity levels by affecting the availability, accessibility, attractiveness, and safety of different modes of transportation. Urban design can also affect the social and environmental factors that motivate or discourage people from being physically active.

One of the ways that urban design can promote physical activity is by creating environments that encourage walking, cycling, and other forms of active transportation. Active transportation is defined as any mode of transportation that involves human-powered movement, such as walking, cycling, skating, or using public transit. Active transportation can provide multiple benefits for health, such as increasing physical activity levels, reducing air pollution exposure, and improving social interactions.

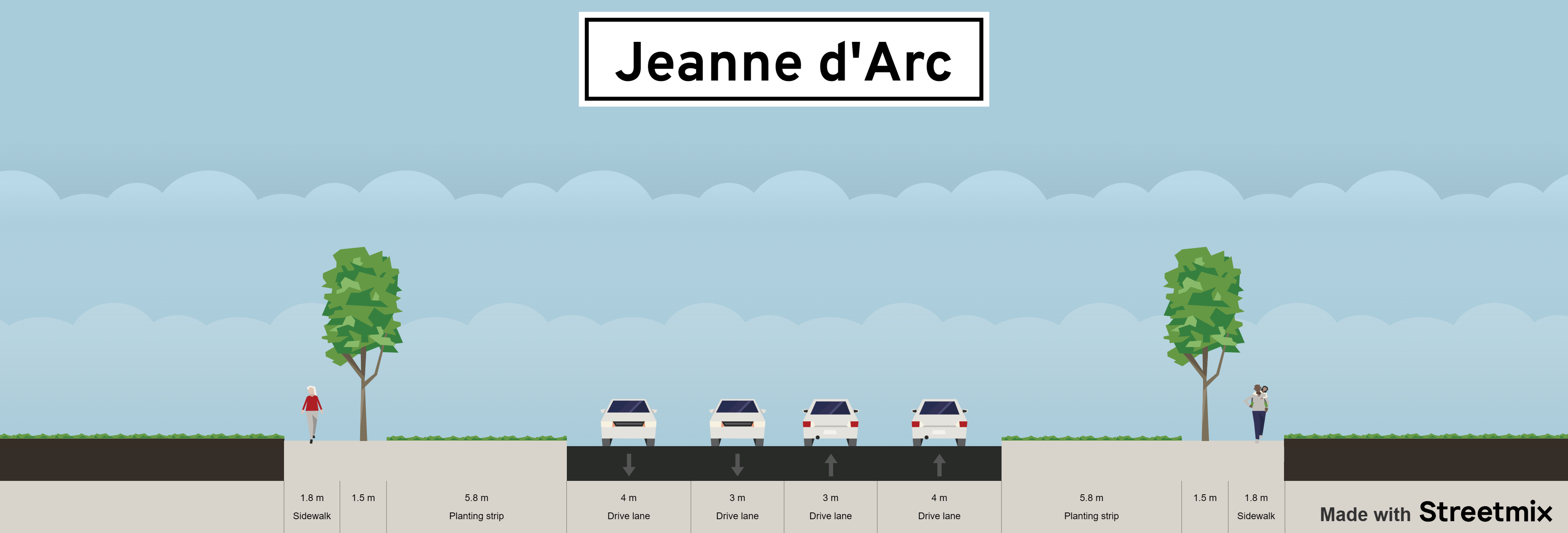

However, many urban environments are not designed to support active transportation. Instead, they are dominated by car-oriented infrastructure, such as wide roads, large parking lots, and low-density sprawl. These features create barriers for active transportation by increasing distances between destinations, reducing connectivity and diversity of land uses, and creating unsafe and unpleasant conditions for pedestrians and cyclists.

Therefore, urban design should aim to create more compact, mixed-use, and walkable neighborhoods that facilitate active transportation. Some of the strategies

that urban designers can use to achieve this goal are:

- Reducing road widths and traffic speeds to create more space for sidewalks, bike lanes, and public transit.

- Increasing the density and diversity of land uses to create more destinations within walking or cycling distance.

- Providing amenities and services along walking and cycling routes to enhance comfort and convenience.

- Enhancing the aesthetic quality and safety of streetscapes to create more attractive and inviting environments.

- Encouraging community participation and ownership in designing and maintaining public spaces.

Some examples of cities that have implemented these strategies are Copenhagen in Denmark, Curitiba in Brazil, and Portland in Oregon. These cities have shown that urban design can increase active transportation rates and improve health outcomes among their residents.

Another way that urban design can promote physical activity is by providing access to urban green spaces, such as parks and gardens. Urban green spaces are areas with natural or semi-natural vegetation within or near urban areas. Urban green spaces can provide multiple benefits for health, such as improving air quality, moderating temperature extremes, reducing noise pollution, and enhancing mental well-being.

Moreover, urban green spaces can offer opportunities for recreational physical activity, such as jogging, playing sports, or gardening. Urban green spaces can also foster social interactions and community cohesion by providing venues for gatherings, events,

and celebrations.

However, many urban areas lack adequate access to urban green spaces. According to a report by the WHO, only 20% of urban residents in low-income countries have access to urban green spaces within 300 meters from their homes. The report also found that urban green spaces are often unevenly distributed, with disadvantaged groups having less access than affluent groups.

Therefore, urban design should aim to create more and better urban green spaces that are accessible, inclusive, and diverse. Some of the strategies that urban designers can use to achieve this goal are:

- Increasing the quantity and quality of urban green spaces by creating new parks, gardens, or green roofs, or by restoring degraded or abandoned areas.

- Improving the accessibility and connectivity of urban green spaces by creating green corridors, trails, or bridges that link them to other destinations.

- Enhancing the diversity and functionality of urban green spaces by providing different types and sizes of spaces that cater to different needs and preferences.

- Promoting the use and management of urban green spaces by involving local communities and stakeholders in planning, designing, and maintaining them.

Some examples of cities that have implemented these strategies are Singapore, Medellin in Colombia, and Vancouver in Canada. These cities have shown that urban design can increase access to urban green spaces and improve health outcomes among their residents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, urban design can promote physical activity and reduce the risk of chronic diseases by creating environments that encourage walking, cycling, and other forms of active transportation, and by providing access to urban green spaces, such as parks and gardens. Urban design can also have other positive impacts on health, such as reducing stress, enhancing social capital, and increasing happiness. Therefore, urban design should be considered as a key strategy for improving public health and well-being in cities.

References